“What is landscape urbanism? Is it a method, a practice, or a result? What does this term mean to contemporary practitioners of landscape architecture?”

“What is landscape urbanism? Is it a method, a practice, or a result? What does this term mean to contemporary practitioners of landscape architecture?”

These were questions that inspired the latest installation of OLIN’s Theoretical Symposium, which I moderated with my colleague Katy Martin. Katy and I both knew that this would be a daunting topic, raising all manner of opinions and added questions, so we broke up the discussion into a few key stages. In the days before the symposium even kicked off, we posed these questions to the studio and collected the answers. On the day of the event, we started things off not with the questions, but with a history of “landscape urbanism”—the people, projects, and practices that influenced the concept and led to the coining and popularization of the term itself. We then suggested four definitions of landscape urbanism and used each as a framework for the studio’s theories and questions:

1.) Landscape urbanism as diagnosis

2.) Landscape urbanism as framework and process

3.) Landscape urbanism as green infrastructure

4.) Landscape urbanism as landscape + urbanism

Our format was straightforward, and our goal was clear: to see if our studio could help clarify a potent but increasingly elusive term in landscape discourse.

The development of landscape urbanism as a theory and practice is the result of an evolving body of work by a number of people. In the 1870s, forefathers of landscape architecture such as Fredrick Law Olmsted and Ebenezer Howard demonstrated how the many environmental problems that plagued American cities could be mitigated by planned open space which served both infrastructural and recreational purposes. In the 1960s, Ian McHarg wrote Design with Nature, the first book to describe an ecologically sound approach to the planning and design of communities. However, it was not until the late 1990s that Charles Waldheim popularized the term landscape urbanism. In his 2006 book, The Landscape Urbanism Reader, Waldheim defines the term as follows: “Landscape urbanism describes a disciplinary realignment currently underway in which landscape replaces architecture as the basic building block of contemporary urbanism.”

Landscape Urbanism as diagnosis

Landscape Urbanism as diagnosis

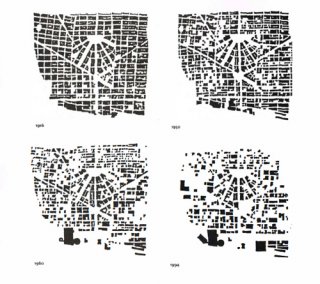

Landscape urbanism as diagnosis relates specifically to Charles Waldheim’s academic analysis of post-industrial North American cities, described in many of Waldheim’s lectures and writings, such as his 2001 book Stalking Detroit. Waldheim describes the existing condition of metropolitan dispersion, which he argues has been caused by the decline of manufacturing, decentralization of transportation, and continued suburbanization. The term further recognizes the emergence of un-designed landscapes in the voids left by dispersion and questions whether the redevelopment of a dense, architecturally defined urban core is possible or even desirable in a declining, post-industrial city like Detroit.

Landscape Urbanism as Framework and Process

Landscape urbanism as framework and process also has strong academic underpinnings but asserts more pragmatically the role of ecological, economic, and social dynamics within cities. In doing so, it critiques both regulatory planning and the fixed, physical master plan that has traditionally dominated urban design. From this perspective, landscape is an appropriate lens for understanding the city not merely because it deals with natural materials, but because it explicitly addresses systems, process, and infrastructure.

The last two definitions of landscape urbanism also present landscape as the framework for urban design, but for different reasons.

Landscape Urbanism as Green Infrastructure

Landscape urbanism as green infrastructure focuses on achieving environmental performance through landscape measures. In this reading, landscape becomes not a metaphor for urbanism but an engineered device with strictly defined functions and measurable benefits.

Landscape Urbanism as Landscape + Urbanism

The term “landscape + urbanism” refers to the increasingly blurred boundaries between landscape urbanism, landscape architecture, and urban design. Partner Dennis McGlade raised the question, “Does this imply the the work of landscape design in an urban setting is new and unique to the modern age? In fact, it is quite ancient.” Partner and CEO Lucinda Sanders, however, linked the emergence of landscape urbanism as a shift in leadership, pointing out that:

“Choices about the form and quality of urban environments have traditionally been made from a perspective of dominance, governance, or finance and therefore from the architectural viewpoint; minimal attention has been given to the complexities of the external environment as a potential and primary generator of urban design. In the world of landscape urbanism, nuances of landscapes and their interface with architectural edges are regarded as influential in shaping urban environments at the least. When most successful, landscape becomes a primary source for making decisions about the urban environment, thereby inextricably intertwining landscapes with architecture. A direct result of this shift is the role of landscape architect as a leader or co-generator of urban design.”

Expressing this tension between transforming and merely re-branding landscape architecture, Landscape Designer Andrew McConnico concluded that “To the extent that [landscape urbanism] encourages the profession and practice to question our motives and challenge our role, it is probably helpful. To the extent that we recycle old concepts, theories and ideas while presenting them as a new movement, it is probably unhelpful.”

The discussion lasted long into the evening and will likely continue at the desks and in the halls of the studio. The next symposium in OLIN’s Theoretical Basis series is a discussion on systems and ecology. We look forward to another great conversation.

new website http://terrakolor.ru/

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE